Here is a paper.

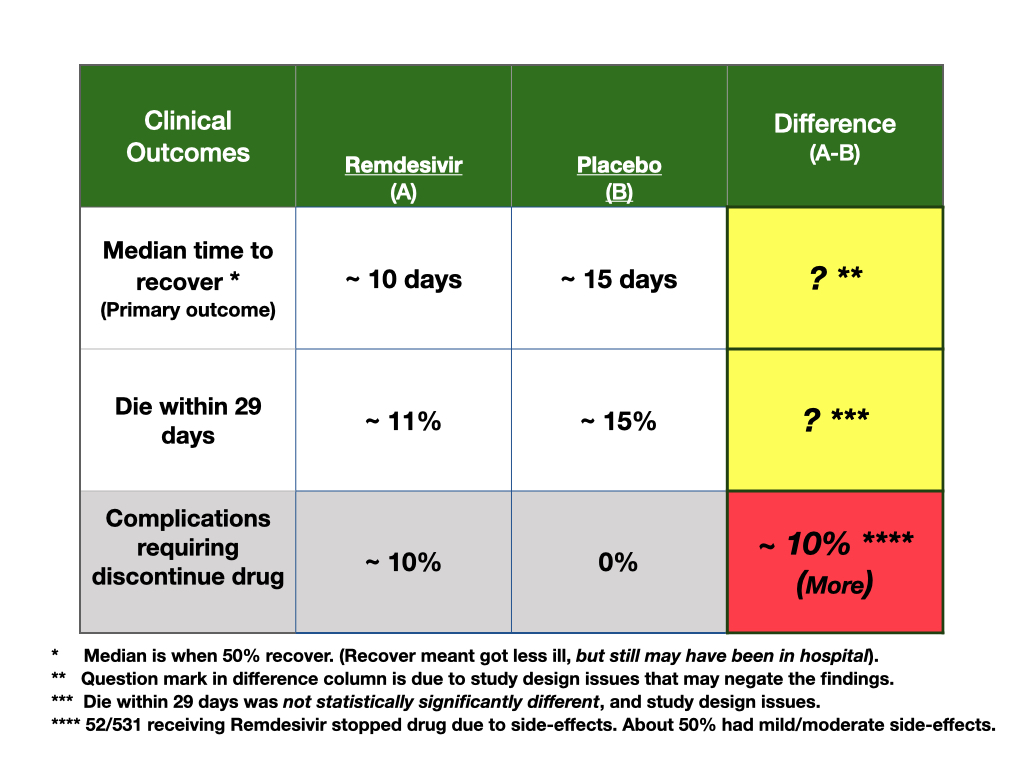

Below is a summary of my critical appraisal of a study regarding a treatment for COVID-19. The patient asking the question is a sophisticated scientist who wanted my opinion regarding the NIH study on Remdesivir. She was not in a position to make a decision regarding treatment, but was concerned the study was not correct. What follows is my response to her query. As a disclaimer, I am a tough reviewer of studies. In my view, NIH studies should be held to high standards; this trial did not do that. This is an unusual post for me and is in response to this patient’s question about the value of the study, not, primarily, about a decision that must be made.

Potential problems with the remdesivir study.

Patients:

- Patients were assigned a clinical risk category at outset, but patients changed clinical risk categories soon after the trial began. This raises a concern about how patients were recruited for the trial. The trial outcomes may be affected by changing population characteristics after the trial started (see imbalance section, below).

- They don’t describe how patients were recruited, nor who recruited the patients.

- There is no mention if patients were chosen randomly, (best), or as a consecutive sample (good), or as a convenience sample (not good). The protocol sounds like recruitment was a convenience sample, enrolling patients at about 60 sites of care in multiple countries.

- Hence, generalizability of the trial may be compromised.

Design:

- The primary outcome measure at the outset of the trial was the distribution of clinical status at day 15. Clinical status was a scale describing patients along a continuum of severity of illness; for example, from being well and home with or without restrictions, to being in the hospital, with oxygen or not, needing mechanical ventilation or not, and, death.

- This was a problematic outcome measure, as patients can change status quickly and move about in the scale. Clinical outcomes do not follow an ordinal, structured path to improvement or decline, outcomes are fluid in nature. In fact, 54 patients were upgraded to worse status early after randomization. Hence the population planned for at outset is changing, compromising the trial.

- The primary outcome measure changed after 72 people entered the trial. This is a problem as the trial was planned to include about 350 for outcome measurement, but now they would have to adjust the power calculations.

- The rational for this change in outcome was unclear; authors stated they had new information on how long people may be ill. This should not matter, however, as the categories were still measurable. All they might have done is change the time of the primary outcome measurement from 15 days to longer, but, instead, they changed the outcome measure. Changing a primary outcome during a trial is not good trial design.

- Trial started in February, but, in March, 22, the primary outcome measure was changed. Only one month later, on April 19, they stopped recruiting for the trial. So about 1/2 time with one primary outcome, 1/2 time with other.

- On April 27th, a data monitoring board reviewed data and stopped the trial early for benefit. This is a big problem with trial design. For example, there would be no agreement on stopping criteria before the trial started on the new outcome measure, as the primary outcome measure changed. Criteria for stopping must be developed before doing the trial, not during or after.

Imbalance in prognostic factors/random error.

Table 1 shows imbalance in prognostic factors. This is a problematic finding for a RCT. Comparing table 1 to figure 3, there are concerns that prognostic imbalance favored the active, drug arm.

The way to evaluate a study for the potential effects of imbalance in confounding clinical factors is to look at the effect size for measured confounding variables, and then compare the number of people with those measured confounding variables who got the active drug versus the number getting placebo. In this trial, the confounding seems to favor the active drug.

For example:

- More women were on the placebo side of the trial (figure 3 shows large variation in effect size due to gender so by chance, more woman may make the active arm look better).

- Those on mechanical ventilation or ECMO had no effect from active treatment. These people did worse and there were 23 additional people (154 versus 131) with this level of clinical severity on the placebo arm of the study.

- If symptoms were present greater than 10 days, there was no effect of remdesivir treatment, and more people entered late on the placebo side, but they do not report how many.

- The biggest benefit, effect size for the drug was noted in people in the hospital who needed oxygen therapy. There were 29 additional people in this category (232 on active drug arm versus 203 on the placebo arm) of the trial.

- While they don’t show us the numbers of people in age categories, age was an important confounding variable, and, the placebo group was older.

So, at least, 23 and 29 more people with favored outcome status by chance were on the drug side of the trial. While these may seem like small numbers of people differently balanced between the study arms of the trial, consider that there were only 11 people different between the study arms (517 people receiving remdesivir and 508 people receiving the placebo) who completed the trial alive or dead at day 29, the end of the trial.

Comments:

The rational for changing the outcome measure is not well supported. It is a critical problem to change the outcome measure during the trial. Planning based on another outcome means statistical manipulations will increase after changing the primary outcome. Adaptive designs have been shown to increase the likelihood of a false positive trial. There were differences in numbers of people and planning for outcome assessments between the protocol (NCT04280705 at Clinical trials.gov) and the final report. Adaptive designs should not be allowed, in my view.

They do not describe how the outcome was measured, and by whom; 6% of patients were reclassified or progressed from mild/moderate status to severe status after the randomization. This means, either, the measure was not accurate, or that patients were changing status quickly making the population being studied precarious for the chosen outcome measure.

They did not measure how well the trial “masked” those evaluating clinical risk scores. At some sites, they wrapped foil over the placebo IV, and the treatment IV, but we don’t know how well that worked. Since the primary outcome requires judgment, like, if oxygen is needed or not, or the patient is in the hospital for a different reason other than having COVIE-19 care, unmasking may have biased assessments. But, they did not measure this.

The definition of “better” in this trial is complex. Better was if a patient ended up in one of three clinical categories, from being well to still being in the hospital.

Stopping trials early is a problem. Simulations and experiential studies show that stopping trials early inflates the false positive rate and overestimates benefit. The stopping of this trial may be especially problematic as conflict of interest is prevalent in this trial. Members of the company who owns the drug were on the protocol team. They were, even, present in weekly protocol meetings. While the NIH folks say they made decisions, they did not say that the views of the conflicted people did not influence them. The NIH, must, in my view, quit cohabitating with those with financial interest.

So, based on unclear samples of patients being recruited, study design issues such as the complex outcome measurement issues, the changing of the primary outcome measurement, stopping the trial early, and random error of prognostic factors, my view is that this is a false positive trial. A false positive trial is one that says something is better when it is not. It is not good enough to accept a trial result just because the NIH did it, got the paper published, and got the drug approved. Higher standards are needed for studies as those study outcomes affect people.

Thanks, great breakdown

You are welcome. Will do more in future. Usually shy away as patients are smarter than doc with information and often make good choices despite unclear data. But, we all need to be more sophisticated at understanding information. lots of bad out there.