I often get questions asking how to determine helpful from unhelpful information in social media or news reports. I have not before addressed this question as my job is to help people make decisions using only the best medical information. Best information comes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or full population studies and includes a numeric assessment of how much better one option is than another while also showing, numerically, how much more risk, or complications may also occur. Making a decision requires a trade-off between added chances of benefit versus added chances of risk.

Ideally, any news or social media report would include the numeric information of benefit and risk from these best sources of information. Unfortunately the public is often fed a steady diet of information that does not fulfill these essential criteria. Myths abound; short, catchy headlines obscure the nature of the information in the articles; reports of poorly conducted studies can still make the light of day of publication in one of the 100s of thousands of journals; an article about masking in children is published in a prestigious, peer-reviewed journal but then retracted on methodology grounds. This cacophony of unhelpful information should, perhaps, be called, messed-up-information, not misinformation.

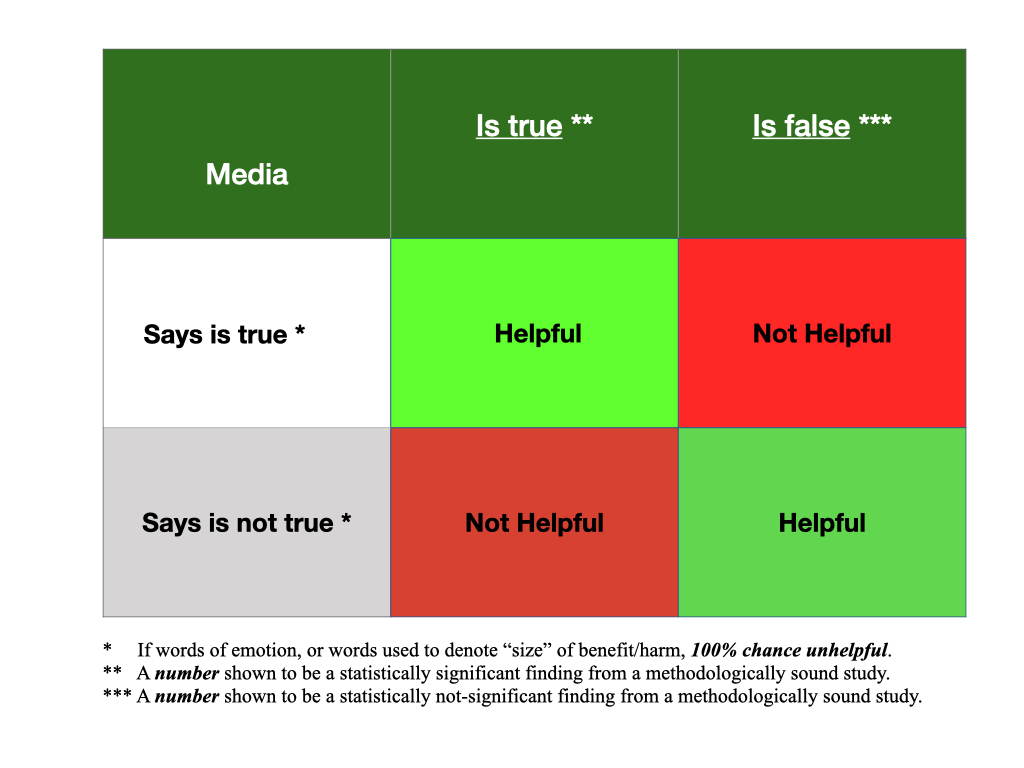

The term, misinformation, is commonly used in today’s media, but, to me, the definition is unclear. Some think the term means the same as “fake news” which means the information is a lie. Others think the term means that true, helpful information is manipulated for biased intent. This lack of clarity makes the term, misinformation, useless. I propose the terms we should use are helpful information or unhelpful information. Helpful information will include numbers from best studies presented in a manner that allows the reader to understand trade-offs between added benefit versus added risk. Any other information is unhelpful.

Little research has been done to test if a person can learn to identify helpful from unhelpful information. I found only one RCT that tested if people who were taught “debunking” strategies would alter their assessments of the value of published information. Debunking means that some study subjects were taught to recognize false information in media reports while others were not. Debunking reduced the chance that people would favor an article in the short run by about 14% over the untrained people, but the effect did not persist. Interestingly, those who supplied a reason for believing what they did were less likely to change after debunking.

So, I can’t provide a scientifically sound study on how to discern if information is helpful or not. But, my definition of helpful information above provides a path. If any of the following are presented in a social media or news report, the information being presented will not be helpful.

-

If the report uses only words, there is no helpful information.

The following words are commonly used in unhelpful media reports.

-

Words of emotion. (Extremely beneficial, guaranteed, dangerous, completely eliminate, natural, boost, cure, revolutionary, rapid, severe, wonderful, quickly, or testimonials.)

-

Words denoting “size”. (Significant, glut, very good chance, some, mild, rare, surge, or soar.)

-

If a report uses numbers without describing how the numbers were measured, or without discussing the quality of the study used to measure the numbers, there is no helpful information.

Numeracy, the ability to contextualize and understand benefit and risk, is the key skill for identifying helpful information. However, some numbers are never helpful.

-

If the number is a relative number (like, 90% reduction in COVID), it is not helpful. The only number that matters is the absolute difference.

-

If the number is from observational studies, it is not helpful. Observational studies are not experiments, hence, information from observational studies may only suggest possibilities, they can’t provide true numbers. A hint for detecting if information is from observational studies is the use of the word, “may”. For example, “vitamin d may help with COVID”. The “may” tells you this is not helpful information.

-

Be wary of “extrapolation” numbers, which are not helpful. By this I mean that a report projects future numbers from present, relevant numbers from RCTs.

I was, my parents told me, a born skeptic. Given the plethora of reports that contain unhelpful, even misleading information, being a skeptic about information presented in the media is a worthwhile character trait. It is best to not read media reports about medical care. Instead, seek the actual reports of medical studies. There are several strategies for finding the actual reports of studies rather than manipulated, poorly communicated media reports of those studies. Strategies include;

-

When doing a Google search on a topic of care, include the following additions at the end of your search, 1) PMID (PubMed Identifier), or 2) :pubmed.gov.

-

Use Google Scholar.

-

Use pubmed.gov to search for medical articles.

-

For cancer care; use PDQ-NCI for studies on nearly every cancer.

It feels to me like the accurate information is drowned out a lot of the time by the sensationalized, inaccurate data presented by media. I’m also often distrustful of the source because it feels it’s motivated by something other (money and attention) than a desire to provide a genuine answer to a question or problem under the guise of helpful information. I feel like this is especially true in recent times with information about Covid.

I once was given an exercise in my technical writing course in college where we were all given the same data set, but asked to make it paint a different picture than it actually does. I.e skew the y axis or x axis of a graph to fit my means, or use different graph variety to represent the data in a way that fits my needs. I feel like I’m often shown numbers to make me trust it, but it’s often depicted in a way that fits the speaker’s need rather than what an unbiased depiction of the data is. For example, early on I saw a lot of different depictions of the death rate of Covid or the efficacy of masks that didn’t show the true whole picture.

With that in mind how can we better discern if we’re being lied to with numbers to make sure we are paying attention to the helpful information over the unhelpful information? Would you say that part of numeracy is being able to recognize when someone is trying to show data in a way that doesn’t accurately represent the whole picture?

I took a course in “graphicacy” that was a blast. It is amazing how many ways data presentations may be manipulated to change perception. I love looks at raw data, like probability distributions, scatter plots for my data looks. Graphs can be so misleading, I would suggest that the only numbers you should entertain are probabilities of outcomes, and the difference. Medicine and science runs on the following, small list of numbers; base rate of event/outcome in control group, rate of event/outcome in intervention group (like masks, etc), and the difference between the two. This goes for both beneficial outcomes and side-effect/complications/harm/risk outcomes. Read only these numbers and slowly, then, learn to discern the qualities of studies. Thanks for your insightful comments.